Buddy

Rich :

"You want to know what I think

of Gene Krupa? Well, where do you begin? Gene Krupa was the beginning

and the 'end' of all drummers. He's a great genius - a truly great

genius of the drums. Gene discovered things that could be done with

the drums that hadn't been done before, ever. I'll tell you about

Gene. Before Gene, the drums were in the background, just a part of

the band. To put it in plainer terms, the drums didn't have much -

meaning. Along comes Gene and the drums take on meaning and they're

out of the background. The drummer becomes somebody, you know? Gene

gets credit for making people aware of the drummer - of what he's

doing and why he's doing it and he deserves every bit of that credit.

Can you imagine jazz without Gene?"

:

"You want to know what I think

of Gene Krupa? Well, where do you begin? Gene Krupa was the beginning

and the 'end' of all drummers. He's a great genius - a truly great

genius of the drums. Gene discovered things that could be done with

the drums that hadn't been done before, ever. I'll tell you about

Gene. Before Gene, the drums were in the background, just a part of

the band. To put it in plainer terms, the drums didn't have much -

meaning. Along comes Gene and the drums take on meaning and they're

out of the background. The drummer becomes somebody, you know? Gene

gets credit for making people aware of the drummer - of what he's

doing and why he's doing it and he deserves every bit of that credit.

Can you imagine jazz without Gene?"

Louie Bellson :

"Gene Krupa was a wonderful,

kind man and a great player. He brought drums to the foreground. Benny

Goodman often said 'Gene was a spark plug that ignited the whole

band.' He was a great natural showman. Gene cared for his fellow man

and past on to others(drummers) his knowledge of the instrument. He is

still a household name, I was privileged to know him."

Louie Bellson :

"Gene Krupa was a wonderful,

kind man and a great player. He brought drums to the foreground. Benny

Goodman often said 'Gene was a spark plug that ignited the whole

band.' He was a great natural showman. Gene cared for his fellow man

and past on to others(drummers) his knowledge of the instrument. He is

still a household name, I was privileged to know him."

Roy Haynes

(legendary jazz drummer) :

"He was such a wonderful

person. He was so different from some other drummers I had known.

Later on when I was with (Stan) Getz, we played the Tropicana in Las

Vegas. Gene was doing a radio interview, and the bass player with us

had heard it. Gene had talked so much about me on the show. That was

very inspiring. He was such a wonderful person and a great master of

the instrument."

Roy Haynes

(legendary jazz drummer) :

"He was such a wonderful

person. He was so different from some other drummers I had known.

Later on when I was with (Stan) Getz, we played the Tropicana in Las

Vegas. Gene was doing a radio interview, and the bass player with us

had heard it. Gene had talked so much about me on the show. That was

very inspiring. He was such a wonderful person and a great master of

the instrument."

Lionel Hampton :

"I have to call Gene a miracle

drummer boy. I compare him with the drummer playing in the Spirit of

'76. I put Gene in the category of not only a great musician and one

of the world's greatest performing artists, but he was also a real

patriot. All the kids used to hear him play and he had a rapport with

them that no other drummer had. The people responded to him and saw

him in a different light. They never compared him to other drummers.

There was always a special, honorable place for Gene. Other drummers

came before him, but when Gene appeared on the scene, he mapped out a

place for himself and became well-respected. It was a great thrill

playing with Gene. He was always my favorite."

Lionel Hampton :

"I have to call Gene a miracle

drummer boy. I compare him with the drummer playing in the Spirit of

'76. I put Gene in the category of not only a great musician and one

of the world's greatest performing artists, but he was also a real

patriot. All the kids used to hear him play and he had a rapport with

them that no other drummer had. The people responded to him and saw

him in a different light. They never compared him to other drummers.

There was always a special, honorable place for Gene. Other drummers

came before him, but when Gene appeared on the scene, he mapped out a

place for himself and became well-respected. It was a great thrill

playing with Gene. He was always my favorite."

Roy

Knapp (world-class drummer & one of Gene's teachers) :

"There is not a professional

drummer, percussionist or other instrumentalist who does not in some

way owe something and should be grateful to Gene Krupa for his

imaginative and creative contributions in the modern drum techniques

and styles in performance that we are using today. He invented and

gave to the world a 'new look' into the progressive studies in the

modern rhythmic patterns for the drums, hi-hat, cymbals, wire brushes,

tom-toms, tympani, mallet-played instruments and accessories. With

Gene's unusual talent and the magnitude of his influence, the reaction

became monumental internationally.

"

Jim

Chapin (teacher/author):

"Like the best of them, he was

able to concentrate on his music and meant what he played. Though his

performances were visually dramatic, the sound of his music was

dramatic as well. Gene was larger than life, a charismatic figure that

made the public fully conscious of drummers. He was so important, it's

almost difficult to talk about him.

Norman Granz (producer

and promoter of JATP) :

"I'll never be able to say enough

for him or about him. Frankly, I was worried at first about him (when he

first joined the Jazz at the Philharmonic tour in 1952). Face it. Gene

is a top cat to the public. He's like Louis and Benny. Tops. So I

figured maybe he'd be a great attraction, yes, but, you know, a little

temperamental. Well, I'd play ball. I said, 'Gene, you want to take a

plane or travel alone or anything, go ahead.' He laughed and said, 'What

for Norm? I'm no better than anybody else.' What happened all through

the tour was that Gene did anything I wanted him to do. And all the

other cats are nuts about him. And I think, honestly, that they play

better with his beat because they like him so much personally. As for

Buddy Rich, finally, I reached the end of my patience with that guy. He

was through, period. I wouldn't have him around, that's all."

"Gene

Krupa: The World Is Not Enough" by Bobby Scott

Eugene Boris Krupa was an

enigma. His tiny frame belied his impact upon the music scene of his

heyday. People could not associate a small man with the sound of his

drumming. It was only after a double take that he was recognized and

entered the ken of the viewer. That was, to him, just fine: he'd spent

half his life living down a "slip" he had never even made.

The Ol Man, as I called him,

in keeping with the tradition of the band era when all leaders were

thus called, never used narcotics, nor could he ever have been in even

remote danger of addiction. As one might try a roller-coaster ride,

once or twice at most, he had tasted them. But in fact they frightened

him, in a way that liquor never did.

In the year or so I worked and

traveled with him, occasionally taking meals with him, we spoke of his

"hitch" two or three times at most. And always it was wrenched up out

of his memory. It was not the recollection of the bars on the windows

and the isolation but the shame of it that troubled him. He said it

changed him inwardly.

He remembered arriving in

prison. "This one screw took me to the laundry, where I'd been

assigned to work, Chappie,"he said. was his nickname for me. "The

screw and I stood there before all the convicts and he said, 'I've got

a guest for you fellas. The great Gene Krupa.' Well, not one of the

convicts cracked a smile. Then he gives them a big smile, don'cha see,

and says, The first guy that gives 'im any help.. .gets the hole.' You

understan' me? He meant solitary. Well... the minute he walks out, all

of 'em gather aroun' me, shakin' my hand, and one of 'em, a spokesman,

says to me, 'What is it we can do to help ya, Mr. Krupa?'"

He chuckled, remembering that

moment of friendship. The convicts knew he'd been railroaded. They

made sure his drumming hands never touched lye or disinfectants. One

afternoon an old-timer inquired of the Old Man, "How long's your

stretch, Krupa?" When Gene told him, the convict retorted, "Geezus! I

could do standin' on my head!" Gene said that was the best tonic he

got behind bars. It made him see things in a jailhouse long view. He

was bush league in that hardened criminal population. He did a lot of

deep thinking while he was "inside". Hard thinking, too. He said that

he hadn't used much of what he learned until quite recently, about the

same time I had joined his group, in the fall of 1954.

That's what I liked about him,

right off the bat. He was as honest as he could be. I had to keep in

mind, of course, that I was a sideman and a kid. I expected he would

hide behind what he was, but obfuscations were very rare.

I auditioned for him one

afternoon at Basin Street East in New York. He had never heard me

play. I had been recommended to replace Teddy Napoleon on piano. He

wanted to see if I could fit in comfortably with tenor saxophonist

Eddie Shu and bassist Whitey Mitchell. We played, the four of us, for

ten or fifteen minutes, and I got a decent idea of the head charts

they had been using. Afterwards, Gene and I talked salary and the

upcoming jobs and travel. Then, out of the blue, he said, "I know

you'd have more fun playing with a younger drummer more in the bebop

bag, but I still think we can make a few adjustments and enjoy

ourselves."

Coming out of a living legend,

such self-deprecation startled me. Yet I knew he meant it. I came away

that day thinking that I could certainly learn something about

deflating my own ego from this tiny, soft-spoken, dapperly-dressed

older fellow.

When you're young, and foolish,

you think every thought that comes into your head is of oracular

origin. But many of one's youthful ideas are of worth. Gene helped me

through a sorting process. His own contributions to the quartet were

insightful, and they came out of his tested experience.

Like all the successful

bandleaders of the 1930s and '40s, he knew his primary task was to

choose the right tempo for each piece. It doesn't seem all that

important. But it is. The tempo can make the difference between

success and failure.

One night in Las Vegas he

picked a tempo for so fast that he couldn't double it. He had either

to play a solo that differed from the recording or slow the tempo.

Though the listeners expected the doubling up, he slowed it as he

began his solo. Very, very infrequently did he make such a mistake.

Although he asked us to play

certain tunes, for the most part he gave Eddie Shu and me a free hand

with new pieces and the arranging of them. Occasionally he'd insist on

something. He wanted us to learn Sleepy Lagoon. When he mentioned the

Eric Coates classic, the three of us threw glances at each other. The

old man reminded us of the melody's rhythmic character. He said it'd

lay well as a four-four bounce, though it was originally in

three-four. When we finally got it into a form, it proved a staple of

our repertoire. Eddie Shu and I would never have considered it.

It was Gene who first got me to

sing, and though the first recordings I made under my own name were

done for ABC-Paramount, I had already recorded a single under Gene's

aegis for Verve. and She's Funny That Way were recorded in 1955, with

Norman Granz as producer. Although the performances I turned in were

hardly what I'd find acceptable today, Gene told me, "You've got to

start some time, Chappie, and it might as well be now."

Gene continued to encourage me,

even insisting that I sing a song in each set of an engagement at the

Crescendo in Hollywood. He told me that he had no doubt I would make a

success with singing and writing, and this amazed me. And then, once,

in a rather serious mood, he urged me to address my thoughts to the

success he insisted was coming.

"The toughest thing in life,

Chappie, is to mellow with success. A lot of people with talent never

seem to be able to handle success." Now I give him high points for

perceptiveness, but when you're seventeen, as I was at the time, you

can't understand such things. Gene meant me to stash the thought away.

He hoped, as he later told me, that I'd begin to set up a value

structure to lean upon when I had to face what loomed ahead. Gene knew

how success can destroy. He had witnessed what it had done to others

what it had done to himself. He remarked upon an imaginary power that,

like a snake, sneaks into your breast and ruins you from within. I

used precious little of what he'd told me as I stumbled and bumbled my

way through the next ten years of my life and proved to myself that

human nature is a disaster.

Gene was, as I've said,

physically small, with delicately shaped fingers, salt-and-pepper

closely-cut hair, and a compellingly handsome face. Though it was

never a strut, his walk told you much about his well-made character.

There was magic in his eyes and smile and, in fact, his very presence.

These attributes made him both a ladies' man and a man's man. Even

kids loved Gene Krupa.

For me he symbolized, maybe

epitomized, the Swing Era; the driving dynamic of his drumming

characterized the whole period.

In the winter of '54-'55 during

an eight-week gig at The Last Frontier, I got an opportunity to clock

the Old Man. I was delighted (and sometimes dismayed, I admit) by his

traits.

In a town flooded with Show Biz

people, Gene was a loner. Though he was always convivial and warm, in

his own genteel fashion, he never let casual acquaintances grow into

friends. He gave me the feeling that he'd rather be home in Yonkers,

New York. It was as if he'd seen enough towns to last him the rest of

his life. And of course there was that question behind the eyes of

every listener. Was he still using drugs? What a colossal bore it must

have been to him, never having been even a casual user. So he kept his

contact with the general public short, and he avoided making new fans

or friends.

He was ritualistic about his

day, which had a shape and constancy. In the earlier hours he took his

meals in his room. He left the hotel grounds rarely, and spent little

time with us, his sidemen. He was troubled. At home, his wife, Ethel,

was entering upon an illness that would take her life before the close

of the year.

A woman who watched us every

night became enamored of him. She couldn't understand his remote

attitude. She cried on my shoulder on several occasions. She was in

her thirties, quite beautiful, and mature. He just had no interest in

her, not even platonic. Finally I took up her cause with him. He

received this intercession in a surprisingly sweet manner. He

discussed her lovely disposition. Then he alluded to home. And his

cleanshaven, tanned face wrinkled a bit. "It'd be wrong, don'cha see,

Chappie," he said.

"Hell, we're on the road, Ace,"

retorted the morally bereft teenager. Ace was my nickname for him.

"Certain things you just don't

do, Chappie. Certain things you just can't live with, son."

When I heard "son", I knew it

was my cue to zip up.

And he stayed to his lone

regimen. After our last set, he always played a few hands of Black

Jack, then started off to bed. On entering the lobby of the casino, he

would play a dollar one-arm. He must have beaten the machine with some

consistency, for he showed me several bags of silver dollars he was

"going to take home for the kids in my neighborhood." He was a

celebrity in Yonkers. There was even a Krupa softball team, made up

mainly of Yonkers policemen and neighborhood friends.

Gene exuded an aloofness most

of the time. But there was no hauteur in it. He never used his

position. He was in fact the least leaderish leader I'd worked for

till that point in my life. And now I think of it, never did work for

anyone after the Old Man; I worked with them. Only Quincy Jones, later

on, in the 1960s, had an ease of leadership that echoed the Old Man's.

Q.J. had gained a fund of respect for his arranging ability, but he

never picked a player who could not cut the charts, nor one he'd have

to "bring along". He was luckier than Gene, who had to put together

road bands, not often peopled with great talents. Still, Gene was

proud of his bands of the past, proud of encouraging and championing

talents like Anita O'Day, Roy Eldridge, and Leo Watson. He was quick

to take a bow for letting new people like Gerry Mulligan write freely

for the band. (Disc Jockey Jump is a classic from that pen.)

One afternoon in Vegas, the

four of us were in Gene's room, rapping. Gene sat on the huge high

bed, his short legs hanging off the fat mattress, much as a child's

would, feet not touching the floor. Eddie Shu, bassist John Drew, and

I sat in chairs semi-circling our leader. The conversation turned to

"serious" music, that is, the written variety of music so often and

incorrectly called "classical" music. (The "classical" was but one

period of "serious" music's history.)

Eddie was talking of his

beloved Prokofiev. Gene introduced Frederick Delius into the

conversation. Having ascertained that we all had a passing

acquaintance with that much-traveled Englishman's music, he sent his

bandboy-valet-aide Pete off to the center of town to buy a stereo

phonograph and every available recording of Delius' music. With a

fistful of large bills, Pete disappeared. We ordered sandwiches and

beer to consume the time. Our anticipation had reached a zenith when

Pete came through the door with a brand new portable phonograph and an

armful of LPs. (Oh for those halcyon days of the 1950s when record

shops had inventories!) That armful of music made the afternoon one of

the most pleasurable I've known. Sadly, one is today hard put to find

a single album of that wonderful music.

I had touched on the music of

Delius with my teacher, but his academic fur had been rubbed the wrong

way by the inept way in which Delius often developed his materials. In

fact my teacher though it "pernicious" to treat one's musical thoughts

in such a lack-a-day manner. I had to admit he was right. But for me

it was a matter of the heart, not the brain. There was a glowing

genius in Delius' vision, his sheer individuality. That uniqueness

could not easily be dismissed. Of course, when you're studying, you

address yourself to examples of lasting structural achievement,

including the engineering of Bach, and, among the moderns, the neatly

dry but marvelous Hindemith. To the teacher of composition, Delius is

unnecessary baggage, ordinarily used as an example of what shouldn't

be done with one's musical ideas.

But Krupa found much in Delius'

music to commend it. He credited Delius, if the English will forgive

him, with developing an American voice, melodically and harmonically.

Gene pointed to a bass figure, a fragment, in the orchestral piece

Appalachia to show us what Delius was "into" in the 1880s. That phrase

shows up in the opening strain of Jerome Kern's Old Man River. Gene

didn't mean to imply that Kern had plagiarized it. He meant only to

show that Kern, like others, was affected by Delius' music.

That afternoon, acres of hours

were consumed listening to 'North Country Sketches, Paris: Song of a

Great City', and the shorter tone poems 'On Hearing the First Cuckoo

in Spring In a Summer Garden.' To my delight I discovered that I was

disposed towards Delius' music, that it spoke to me of my self in an

odd and mysterious way. It also offered relief from the rhetorical

now-hear-this quality of the Late Romantic literature that consuming

desire of composers to out-Wagner Wagner. Since that afternoon, I have

read a learned critic's assessment that I find marvelously on the

mark. He placed Beethoven as the dawn of the Romantic Era, Wagner as

its high noon, and Delius as its sunset. There is a point that has

been made before that still bears emphasizing. Delius, unlike Wagner,

never rages. It is his understating that draws his listeners. Though

other composers have captured nature in her glory, with splashing

colors that cover the score pages, none has captured her tranquility

as Delius did. No one.

Krupa pointed to the folk-song

elements in the last scene of the opera about miscegenation, Koanga,

insisting, quite correctly, that Delius was years ahead of other

composers, Gershwin in particular, in using what can only be termed

American materials - those materials we've come to associate with

jazz, blues, and popular music. This is no doubt a startling view to

the many English fans who find Delius painfully English, a star

brightly shining in the Celtic twilight. But Delius' own inclinations

drew him to the ground-breaking American poet Walt Whitman, whose

texts he used for 'Sea Drift' and 'Once through a Populous City.'

Krupa was astonished that

Delius could have been born of Dutch parents in Bradford, England,

write his marvelous early music in the United States, live the better

part of his life in Grez-sur-Loing in France, and speak nothing but

German in his home. Gene revealed a hitherto unseen excitement in

putting the composer's life before us. (He would later laugh on

discovering that I shared Delius' birthday, January 29.)

It was the longest non-stop

conversation I'd had with him, and he began opening up some of his

memories. He spoke of a time when he was a kid, playing in a speakeasy

in Chicago. It was brought to his attention that Maurice Ravel was in

the audience. History, it seemed, had stepped right on his toes. That

visit started another love affair for Gene, one that culminated in his

recording of Ravel's 'Bolero in Japan.' The recording was never

released because Ravel's one remaining relative, a brother, sat

heavily on the composer's estate. Gene never did tell me what

departures he'd made from the score.

Most surprising to me, as a

student of music concerned with its historical periods, was Gene's

knowledge of what had gone before. Even as a kid, he said, he'd been

interested in and inclined towards "serious" music. So were his

confreres. Wasn't Gershwin a departure? he'd ask. And what of Paul

Whiteman's efforts? He'd laugh that chuckle of his but never allow

himself a guffaw. Then he'd draw attention to the obvious differences

between the freer jazz playing and written music. Having been in the

pit band put together by Red Nichols for Gershwin's 'Strike up the

Band' on Broadway, he had more than an adequate idea of how the

wedding of the seemingly disparate elements of the "played" and

"written" was to be effected. Among the movers of his generation, he

was one of those who favored the marriage of "serious" music and jazz

and never disparaged attempts at a Third Stream. This was of enormous

value to me, then, because I leaned toward it myself. Once I mentioned

Stan Kenton. Gene commended the adventurous nature of what that

California orchestra was doing. But he was put off by the martial

quality that came from those blocks of brass. He was not disposed to

the materials, either, preferring the work of Woody Herman's and Duke

Ellington's bands.

I wonder now whether there'll

be any more Krupas or Woodies or Dukes. There may not be, in fact.

Will they be missed? 'I' will miss them, mused the war-weary typist.

We've witnessed the battle of the camera and the turntable over the

last sixty years, and though the phonograph record/tape has made

enormous strides, they are small beside the gains of motion pictures

and television. Not to mention that there no longer are dance halls

and cabarets, and there are too few jazz clubs. The extinction of the

latter means there'll be no places to woodshed. For the new recording

artist, the making of an album is not the end but the beginning of a

now-larger process. The videotape of the song, the actuating of it, is

the new culmination. There lies the defeat. The LP was a complete

parcel of entertainment. The pictures you saw were of your own mind's

making, like the fantasies of the young. Sinatra sang a song and you

saw the face of your own loved one in your mind's eye. added the

lazily falling snow when Nat Cole painted a warm familial setting in

'The Christmas Song.'

No more is that the case. It's

as if a great bell tolled the knell of all that was musical and

precious. What must it be like to be raised with the "pictures" on the

boob tube?

Bill Finnegan once predicted:

"Soon, people will be dancing by themselves in ballrooms and clubs."

He said it in the old Webster Hall RCA studio, now gone, to Larry

Elgart and me. It made us shudder, then laugh shallowly. How else

could two dinosaurs react to their own imminent extinction?

Krupa tried his best to keep

his band alive. "But going to jail," he said to me, "meant going

through one fortune I'd saved and it took darn near another one to put

it back together again." Worse was the damage to his morale when, in

order to reinstate himself, he had to become a sideman in the Tommy

Dorsey orchestra. Though he respected Dorsey's musicianship immensely,

"I couldn't stomach the man, personally, Chappie. Too self-centered."

Being a glamorous ex-con of newsworthy status, Gene no doubt brought

out as many people as the band did.

Somewhere on the path he was

traveling, it became clear to him that he needn't bother leading a big

band any more. After the stay in jail, he said, he found he'd lost the

degree of understanding necessary to be surrogate father to a group of

young players. "The problems never end, Chappie. Musicians are great

human beings, but face it: we're all kids! And I don't mean Boy

Scouts, either."

The other side of it was that

Gene didn't have the inclination to adapt to small-group drumming

either. He tried, sure, but night after night of restraining oneself

is not fulfilling. He'd smile and say, "Tonight, the way I feel, I'd

love to have sixteen guys out there with us...and push the walls

back!"

He was frugal, but I overlooked

that because he wasn't greedy. The two years I was with him, though,

were a searching time for him. He told me straight out that he was

looking to make a deal for the rights to his life story, hoping that

the movie monies would provide for him in his slow autumn walk. When

we worked Hollywood, he was always in the company of a screen-writer,

retelling the story. It took a toll on him. The memories no longer had

any sweetness for him. Confronted with the residue of his past, he

found himself unable to bring order to it. There was always a 'Why?'

on his face, though he hadn't an inkling that it was there.

By the end of the Vegas gig,

we'd worked out every wrinkle in the group and could have sleepwalked

through the performances that month in California. Norman Granz

recorded an album with the new group, which now featured the

English-born (and now late) John Drew on bass. Thus for the first time

I got the chance to hear the group "from out front", as it were. I was

brought down by my own work, but the Old Man had a better knowledge of

how talent matures, and he encouraged me, bolstering my sagging ego.

On one ballad I played so many double-time figures I could only say,

"Why so many goddamn notes?" Gene said, "It'll all come together one

day, Chappie. But it won't if you don't go at it seriously." I told

him I thought I sounded like a guy killing snakes with a Louisville

Slugger. "What do you think people want to hear?" he said. "Lullabyes?

Hell. Keep on playin'with that kind of drive. It'll come together,

don't worry. You've got a good problem. You've got more energy in one

finger than most piano players have in their whole body."

I perceive now that acting as

Gene did responsively is the largest part of leadership. What he

offered wasn't unqualified back-patting but an attempt to infuse

bristling youth with a dose of much-needed patience. It was within his

capabilities to understand my adolescence. Why, I'm still not sure.

Oddly, he'd had no experience in child-rearing, never having had a

family of his own.

Gene was a product of his own

making the self-made man of American myth. But is it myth? And who,

having witnessed the unexpected emergence of talents of such large

artistic dimension, could not applaud jazz for serving the commonweal,

as the Church of medieval times raised up the peasant-born to the

penultimate seat of power and influence? Jazz is truly a wonder of

magnitude. It can even make a piece of well-wrought written music

sound quite parochial. When Gene Krupa and the other burgeoning

talents were confined to bordellos and speakeasies, the heartbeat of

the American experience remained in limbo. But once the hats of

respectability were tipped as jazz passed by the reviewing stand of

life, the system proved it could loose the sources of its strength.

What a terrible reminder to the social scientists, too to find out

that it is neither our minds nor a polling place that brought us

together. It is shared aspirations in the same language that does it.

Regionalism. Nonsense. When Louis Armstrong ventured north, bringing

his New Orleans-born "Dixie", he found a Chicago version, a dialect of

the music, already in existence. Jazz had proved it is the

homogenizing influence, and the social historians have myopically

passed over this fact.

When you enjoy the people

you're playing with, you naturally perform to your limit, and

sometimes even touch on the tomorrow side of your talent. I grew while

I was with Gene's group. But by the end of a year and a half, I knew

it was time to move on. And so I took leave of the quartet. Such

partings were familiar to a man like Gene. I was pregnant with ideas I

had held inside for that period of playing and traveling. I learned a

lesson from my grinding dissatisfaction: the score pad was where my

talent should be directed. In a musical sense I had, to my sadness,

passed the group by. I couldn't go back, either. Writing was the way

I'd begin making my own personal history, and I am reminded that the

most important events in an artist's life are those that transpire

inside oneself, the invisible journeying and mental mountain-climbing.

Artistic endeavor is reduced to a war between two or more parts of the

self. The playing of jazz was at that point too diverting. When you

play every night, you don't listen to what others are playing. And so

I became a listener and reaped the rewards of hearing others speak.

I would have loved to have done

some writing for Gene, had he seen fit to record a special album. But

it was not to be. Gene looked on recording as something worth only

perfunctory effort. "It's dollars and cents, Chappie." He thought that

his name or likeness sold the albums; what was the point in loading up

the initial cost?

In that year, 1955, the Old Man

settled before my watchful eyes. He was in his fifties and secretly

unhappy with what was happening to his life. He never gave me the idea

we were doing one thing of productive purpose, other than pleasing

ourselves. The audience was an invited undemanding adjunct. It was as

if the Old Man knew the hotels and clubs were paying for his celebrity

and little else. We drew the head of the Nevada State Police narcotics

squad. He came in night after night to watch for dilated pupils.

The Jazz at the Philharmonic

tour that fall lifted Gene's spirits, at least for a while. But the

traveling paled them. I often watched that pointless drum battle with

Buddy Rich on every concert, and wondered what it was doing to his

ego. Buddy was like some great meat-grinder, gobbling up Gene's solos,

cresting his triumph in traded fours and eights and ending with an

unbelievable flourish. Gene took it in the finest of manners. He

didn't think music had a thing to do with competition. He had a way of

carrying himself correctly when he walked on, and used that strut of a

sort to the fullest at the close of those demoralizing drum wars. I

broached the subject to him once. Just once. "Anyone playing with Bud

is going to get blown away, Chappie. And remember, the audience isn't

as perceptive as you are." His answer was matter-of-fact, with no hint

of malice.

No one cared less than Gene

about press notices. There is a danger in listening to what is said

about your talent by non-players. Gene never gave them even a

momentary attention.

I let him down one night in

Vegas. I got thoroughly sloshed and had to be carried out of the Last

Fronter. And who did the carrying? You guessed it. Gene tried to get

my six-foot-one through the outer door sideways and ran my head and

feet into the frame. It served me right.

After that night, I was cut off

in the Gay Nineties room. But Gene, a merciful judge, saw to it that I

could have a taste in our band room. And he never counted my drinks.

He accepted that everyone slips, and he didn't carry your mistakes

around inside him. What I did was one occasion to him, nothing more.

I believe his Catholicism kept

his judging of others to the minimum. If you made an apology, he

cleaned the slate. But then, Gene never chalked a thing like that on a

mental blackboard in the first place.

His wife Ethel had only

antipathy for musicians, seeing them as wayward and malicious little

boys. Wonder of wonders, though, she liked me very much. As young as I

was, she thought my lapses were excusable. Not so those of Gene or

Eddie Shu.

One afternoon, when we were

already late getting on the road for a gig in Connecticut, she

insisted that "this young fellow have a sandwich" before we left their

Yonkers home. Gene bitched about her "mothering concern" and the time,

but he didn't get the last word. I was made to "sit down and eat it

slowly." She was a fiercely dominating person, and I did as I was

told. My colleagues in overcoats grumbled through clenched teeth as I

finished the repast in record time and she told Gene to take better

care of the "kids" working for him. "A good meal'd kill that skinny

kid," she said of me, digging at the Old Man. I figured that once we

were in the station wagon and on our way, I'd hear about it. But he

didn't mention it. Months later I asked him about that little scene.

"Better she's on your case, Chappie, than on mine,'" he said with a

chuckle. By then I had witnessed a few of her verbal assaults on him,

particularly when we brought him home behind a pint of Black and White

scotch. But I never heard him bad-mouth her. Not ever.

Then, during the JATP tour, he

became very detached. His eyes seemed far away in some other time and

place. I asked about this obliqueness, and the conversation turned to

Ethel. "She's very ill, Chappie." He stared out of the plane's window

into the infinity of space, as if trying to decipher a future out

there, his handsome face screwing up, the eyebrows knitting. "The

doctors are lying to me. They say she's got an inner-ear infection.

She's got a problem with her balance, don'cha see? But I know. It's a

brain tumor."The last four words bled out of him. I let the subject

lie there where he'd dropped it, and made useless remarks about

worrying not meaning a damn thing, then pushed the button on my seat

and reclined, feigning that nap time was upon me. We never spoke of

her again until the day she passed away.

With all the trouble being

married to Ethel entailed and I got a notion of how hard she had

tried him when they were divorced, from people who were close to him

he remarried her to put himself back into the Church's fold and to

enjoy again the consolations of the Sacraments. To people outside the

Church, the remarriage was viewed as a disaster. It smelled of farce.

To the Old Man, however, it was all quite simple: he had contracted

with God to him a living God, a caring God, a right-here-and-now

God. No amount of worldly knowledge, no rationalization, could alter

his moral position. I certainly wasn't going to question the right or

wrong of it. Gene believed it idiotic to take wife after wife, praying

to hit on the right one. I tended to agree with him. Now of course I

am convinced that the ordinances and Sacraments are not to be taken

lightly. But even at the time, it struck me, this moral posture of

Krupa's, that doing the right thing doesn't always make one feel good.

And the difference is all one need understand to gain insight into the

Old Man's decision. Life shows us, only too often, that what makes one

feel good is not necessarily right for us. I need only mention booze,

of which I have consumed my share, drugs, and promiscuity.

I was made to see, in a clear

and distinct way, that there are higher laws and hard pathways. The

world, of course, applauded someone who extricated himself from a

"bad" marriage. Gene knew that. But he also knew that one cannot

change one's mind except they step outside the Church's comfort. So he

remarried her. He could not take the easier road because of his deeper

commitment to his beliefs. Odd. Keeping a promise isn't worth much

anymore, is it? But the Old Man was right for himself. The life

outside is a consensus affair at best, and nothing in the streets does

a wise man use except so far as he is disposed to make a hell of his

morals and existence. It is always the will of men that disrupts

things, no matter how politely one wishes to view one's fellows. We

are responsible for making cesspools of our lives. What Gene bit off,

he chewed.

He gave me the impression that

he'd had a hell-raising youth. That this was in contrast to the

behavior of his devout Polish Catholic immigrant parents hardly

merited comment. He mentioned a younger brother, apple of his mother's

eye, who disappeared. Gene said his brother was "beautiful". There was

a suggestion that some deranged sexual pervert had abused and then

disposed of him. But whatever happened, no trace of the boy was ever

found. And this put Gene in a strange position in the family.

In strong Catholic tradition,

every family "donates" a son or daughter to the church. A tithe to the

cloth, in a manner of speaking. After the brother's disappearance, the

family's eyes fell on Gene. And he was suddenly in turmoil. He had

tastes for both the world and the spiritual. But in accord with family

wishes, he spent a term as a novitiate in a seminary, during which it

became clear to him, he said, that he was not worthy enough to wear

the collar of the priesthood. His faith never faltered; but the muddy

waters in which he found himself swimming didn't seem to be clearing.

And at last he decided against going on.

In 1955, his rocky Catholicism

embarrassed me, even though I sensed that it was only a matter of time

until I would be confirmed in my own beliefs. But in those days,

sitting in the front seat of the station wagon, hearing him braying at

the words of some evangelist leaking out of the radio, his speech

slurred by scotch, froze me. "There is only one true faith!" crowed

our leader. Eddie Shu, a non-believer, took no umbrage at this, but

Gene's intractable position abraded my liberalism, my

live-and-let-live view of things. The only church-going I had done as

a child was to an Evangelical/Reformed Lutheran church, a dissenting

sect, to my mother, a closet Catholic of no small dimension. It was

only in the last year of her life that she let me know her secret: she

had always gone to Mass, unbeknownst to all of us! My father had left

the Catholic fold and communed in a Presbyterian congregation.

And he and my mother, being at

odds, let their children practice whatever we chose to, or not at all.

But to Gene, the Church

strictures were the bottom line, whether you met that standard of

behavior or not. He felt the Church itself was an empowered instrument

of Almighty God. Now, having put much study into the subject of

validity that split the Christian world in the late Fifteenth Century,

Ive come to see Gene's view the Church's position as regards the

Apostolic continuance and tradition as correct. But in 1955, the

constant harping on the one and only true faith really upset me.

No matter what Gene had done in

his life, what profession he had pursued, his faith would still have

been his rock, his consolation, and his hope. He was not a

proselytizing zealot. He honored everyone's right to feel, to believe

or not believe, in a manner consistent with one's own judgment. The

syncretic form of Catholicism I came in time to embrace would be too

"mystical" and too free-thinking too "apologetic" in the theological

sense - to suit the Old Man. He was hide-bound, for he credited the

very existence of the Church as proof of its magisterium.

I was then fascinated by the

writings of the convert Trappist monk Thomas Merton. Several of his

other books were published after the success of his autobiographical

'Seven Storey Mountain.' Always I bought two copies of his books, one

for myself and one for the Old Man. I was never sure how much of

Merton's mystical approach Gene took to heart, but Merton's abiding

commitment consoled him.

For many musicians, music

either has become or simply is their religion - - the way through

which their deepest feelings are loosened and brought to the surface,

hopefully transfigured. There is a substantial value in this, although

the according of too much value to a means to an end is often

self-defeating and diversionary. What lies within one is not always

enchained for wrong reasons.

I have come to believe through

thirty years of writing music that there is at its source the

revelatory. Simply, I believe there is something else, outside or

inside me, that plays the major role in the process. No doubt

everybody who "creates" feels the otherworldliness of the process. The

mysterious is never farther away than the next blank bar on the music

pad. The real trouble comes when one is forced to ascribe authorship.

To please my own doubts, I have come to think of myself as an

instrument through which someone else's music is played. I am an aide

and abbetor of the spheres' ever-present sounds. If I be graced at

all, it is in being able to hear in the chaos a hint of form and an

incipient beauty.

Gene had no such grand

pretentions. But he did see, as I do, a relation between spirit and

sound. To ascribe a special grace to music wasn't what Gene would do.

In fact he saw music-making as one of the many joys provided by

Existence, i.e. God. For Gene, the religious state known as grace came

only to those who found it of the utmost importance in their lives.

His own faith struck down worldly measures and made his own success an

anomaly to him.

I don't wish to mislead those

who may not understand what being a Catholic of Gene's order entails,

nor its salient characteristics. To Gene, making a friend unhappy had

a direct bearing on how he thought he appeared in God's eye.

There are two seemingly opposed

traditions in the written and oral history of the Church. One is the

Pauline position. For St. Paul, reason, the use of the mind, was of

little value to the discovery of faith, and at its worst an instrument

of deception. He came down hard on the side of faith free, faith

unencumbered, faith rooted in the fact that the "gift" Christ gave on

Calvary had only to be believed and the inheritance collected. To

Paul, the Passion and the Sacrifice cleaned the slate for Mankind with

God. Then there is the Augustinian view, which is: God, in His wisdom,

would not have created an entity as glorious as the human mind if it

was not to be used to seek him! Therefore faith, through the use of

the mind, must be able to withstand the assaults of reason. Fire to

fight fire, as it were. In fact faith should be ennobled by the very

process of reason.

These two positions were what

Gene and I split hairs over, whether he knew it or not. I admit I

envied him his faith. He saw my journeys as escapes into "esoterica"

and, at best, "Words, words, words, Chappie." But then we needed

different things. He was one of the fortunate believers. There are

myriad pathways to faith, and I hadn't taken an easy one. But then no

one gets to pick his path. Sometimes in my despair I feel with

Nietzsche that "the only Christian who ever lived died on a cross."

Ultimately we are shaped by our surrender to God's will.

The uneasiness that all devout

people experience when the rules of men are imposed on them laid no

less heavily on Gene Krupa. The optimism and idealism of the Christian

ethic are burned by this worldly existence, with all its exigencies,

into a smouldering relic. Morality mutates, and is no longer sound,

and right or wrong are determined by the context. Subsequently, one is

hard put to judge if religion doesn't further alienate the already

alienated. Considering Gene's outlook, I am forced to say his rooting

in the Church was both a boon and a bane.

The prophet of Islam was asked

what was the one way to be secure in the eyes of Allah. "Speak evil of

no one," he replied. Gene observed that rule, though he had no

commerce with the thought of the man born in the Year of the Elephant.

Whatever the Old Man felt about people, or questioned, it never got

past his well-tended front teeth. His fairness rested on his

acceptance of everyone's individuality. The confusion made life

colorful to the Old Man, and he would never have endorsed uniformity.

He was so sensitive to the

sensitivities of others. Once I tried to get him to come to my home in

Westchester, not far from his modest house in Yonkers. He made every

imaginable excuse for not coming. Finally I forced him to tell me the

truth. And it was this: He felt that his emphysema would put us off

our food. His wheezing by then had become constant. I couldn't get him

to believe that it would not matter to us. He wouldn't budge. I told

my wife why he wouldn't come. She was mystified. He was concerned what

our kids might think. Such was the height of his deference. Such is

the pride that lives in that tiny man, I told her.

Gene was a man who loved family

life and had none of his own. He was sterile. It is impossible to know

what damage this had done to him. He told me of trips to doctors and

of ingesting substances supposed to make him potent. He even tried an

extract of steer's testes. Why a man wants to go on in his progeny is

something I have no ready answer for. It is too deeply encoded. As a

way to defeat death, it would have little charm for Gene. He believed

in eternal life as promised by God. But his sterility affected him.

When on some occasion a conversation turned to manly prowess, Gene

deprecated himself, resolutely assigning himself the last place on any

list of great lovers. He poked fun at himself. How he came to grips

with all this, I do not know. And to make things worse, his conviction

for a narcotics offense he did not commit ruled out his adopting

children. It was only some years later after my time in his quartet

that with the aid of the Catholic Church he finally did adopt two

children. And as life would have it, they were his only regret when he

passed away, for he had separated from his second wife and had only

visitation rights to quell his anxieties.

"Geezus, Chappie, I adopted the

kids so they'd finally have a home and family. Now they're shifted

back and forth between us. What the hell did I go and do?"

It was the only subject we

discussed during our last telephone conversation. He still would not

break bread at my house, but he offered me a seat in his box at Shea

Stadium to watch his beloved Mets. I couldn't get him to move on to

another topic. He felt he'd let the kids down. No outs or

rationalizations for Gene. And he said he had misjudged his wife,

forgetting that "old men don't marry young women unless they're ready

for problems." I tried to argue around things, but he'd have no part

of it. "I'm a grown person, Chappie, and there's no excuse you could

come up with that'd be good enough to get me off the hook. I made the

damn mistake an' I'll have to live with it, and make the best of a bad

situation." He paused, the portentous silence alive between us on the

telephone line. "There's no one to blame...but myself, Chappie."

The worst part of writing about

a departed friend is that you begin to miss them. It is painful. We

may be ships that pass each other in the night, but don't overlook the

great wakes we leave, and the affect, long after, of the ripples.

You don't get to know a person

like Gene Krupa without gaining insight into the conflict between

worldly goals and personal moral imperatives. I saw this private war

from a near vantage point, and what became clear was that he was a

complex man with absurdly simple needs and desires.

When a man of reputation says

little about what is going on in his own profession, one may assume

that he has critical opinions he deems better left unsaid. But that

wasn't the case with Gene. It was rather a matter of his incapacity to

pass judgment upon what others did, or did not do. When Gene offered

praise, as he did on one occasion for the marvelous drumming of Art

Blakey, he always prefaced his remarks by disqualifying them as

objective evaluations. They were purely an expression of his taste, he

said, and subjective. I asked him why he didn't make judgments of

other drummers. It'd be pointless, he answered, to judge what it was

they were doing if he wasn't privy to what it was they were aiming

for. He refused to be presumptuous. And he never deviated from that.

We were listening one afternoon

to an old album of his big band. He was extolling the arrangement and

the arranger. I didn't care for the piece and said so. "Ah, but

Chappie," he said, "it didn't set out to bowl everyone over. But what

it set out to accomplish.. .it accomplished."

I told him, straight out, that

it was second-class arranging.

And his eyes took on that

twinkle. "Now," he said, "if you'd have written it, Chappie, I'd call

it second-rate, too, because you've more to say than this other

fellow." I didn't hear this as flattery. He wanted me to understand

that there is perfection even when the journey isn't to the polar

caps; that there is as much virtue in being featherweight champ as

there is in being heavyweight champ. "Where your writing is taking

you, Chappie," he said, "the air is very thin. A fall from up there

can kill you."

It was such challenges that he

offered to one's mind. Just when I thought I could easily say that the

Old Man was only capable of seeing things simply, he'd turn the

tables.

It is rare for an artist's

personality to rank with his work. There are thousands of volumes of

biography that do little to illuminate, though they paint disturbing

personal portraits. It is as if the biographers were screaming out a

desire that the artist reach in his life the perfection of his work.

But the artist is precisely the one whose personal life is likely to

be a disaster. Why else would he seek beauty and try to encapsulate

it? This applies to "creative" people. But the "re-creative"

individual, like Gene Krupa, doesn't suffer from involuntary surges of

newness and individuality or visions of the unattainable. It is within

the power of such a person as Gene to enjoy life, to accomplish things

he never thought he could. It is sort of a middle man's role, but it

is not without degrees of freedom that, say, a symphony player never

knows. Krupa could add to what was happening, join his oar with

Gershwin's, as he did in the pit band of a Broadway show, or give a

Mulligan a chance to write. These achievements were the brickwork of

his ease and fulfillment. I am sure he enjoyed the knowledge that he

had helped me along the way.

It is a fact that he partook of

that special world of dreams that made the usualness of day-to-day

living a bane to him. It never sat on him as heavily as it might a

creative person, whose visions never sleep, but he had tasted it, and

one is never the same after that. My father called the world of music

the only way one could glimpse paradise while still alive. He said

that once you had looked through that portal, nothing in the world

would ever mean as much as it once did.

Gene knew his limitations

better than most men, and handled them in worthy fashion. Though he

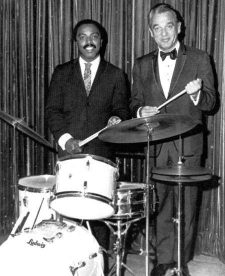

wasn't a pedagogue, he liked to teach, and had many students in the

school he ran with his friend Cozy Cole. Teaching rudiments gave him

the greatest pleasure. He knew that their mastery was the only way to

escape frustration. "Too many ideas, Chappie. These kids got too many

ideas an' no tools to realize them with. It's everybody's problem in

the beginning." He played no favorites among his students. Kids with

little or no gift got a share of his joy and encouragement. The sheer

making of music was Gene's end-all and be-all. If you could play well

enough to play with others, by his reckoning, you were a lucky person.

The last years of his life

found him in the grip of leukemia. It doesn't take you in one swoop;

you just feel it tapping your strength away, daily and monthly. True

to his stylish and graceful way, he made light of it to me, saying

he'd live with it. Being unable to get him out of his home, I decided

to drive up to Yonkers and surprise him. At the time I had several

pressing writing chores and I couldn't get a day to myself. My mother

called to tell me not to go up one particular day because she'd heard

on the radio that Gene had checked himself into a hospital for

transfusions. She said it wasn't bad, though.

The next day was Sunday, if

memory serves me. She called and said he'd gone home and was in

satisfactory condition. Then she berated me for not making time to

visit him. Well, I missed going the next day too, waking late on

Monday afternoon after writing almost all night. But on Tuesday

morning I was up like a shot, bathed and dressed, and starting out the

door when the phone rang. It was my mother.

"What are you doing up so

early?"

"I'm on my way up to see the

Old Man."

There was a long pause and her

sigh cut into me.

"Don't bother, son. He passed

away last night."

She then read me out in her

inimitable fashion, reminding me that friendship is a damn sight more

important than earning a living. I finally slowed her down by

reminding her that I was a grown person.

I went with her to Gene's wake.

I can still feel his tiny hands under my own hand, the fingers

intertwined with a Rosary in death's repose, as I said a prayer and

squeezed my good-bye to him in the coffin. Charlie Ventura broke down

before the bier, words fighting tears in a near holler. "You made me

what I am, Gene. I'd be nothin' except for you! Nothin!

I looked toward my mother and

caught her brushing a tear away.

"He wasn't too bad a stepfather

to you either, Jocko."

Copyright 1984. "Gene

Lees' JazzLetter."

The following are

some of the great letters I have received from visitors to this

site:

Mike Breneman :

"Thanks for the great

page. Gene has been my musical "IDOL" since I was a kid.(I'm now

47 !) I met Gene 3 months before he died in Chicago while he was

performing with the Goodman Quartet. I actually went on the stage

and got his autograph !!!!! The concert was at Ravinnia near

Chicago,an outdoors gig. The place was packed. They did

Sing,Sing,Sing and Gene,even with the pain he must have been in,

flat out, brought the house down !!!! He was a real

gentleman,excellant musician,all around super guy."

Philip Dossick

:

"Shawn, you've done

something very important: remind the world just what a great artist

GK was. When I was 16 years old, I had the great good fortune of

studying with Gene at the school he ran with Cozy Cole. I was with

him from '56-57. And that experience remains the most treasured of my life.

Unfortunately (for me), I did not continue as a musician, and left

the business in '64. But the lessons that man taught me, about love

of learning, love of craft, and true humility, have guided me ever

since. Example: My lessons with him were on Fri afternoons, at 4pm

(after I got out of high school). When we were finished around

5-something one day, he decided to walk me outside as I headed for

the subway home. He asked me if I was headed uptown (Manhattan), and

I said no, I was going to get the train to Queens. I don't know what

possessed me, but I asked him, "Where are you headed?" And that's

when he absolutely floored me. He said (words to the effect) "I'm

going to MY lessons." I said, "What?" And he explained that he was

still studying, with Saul Goodman, the tympanist with the NY

Philharmonic! The master was STILL TAKING LESSONS! This was after

his greatest days and greatest accomplishments were behind him. He

was still eager to learn! There was not a SHRED of "I already know

it all" in him. In fact, he seemed genuinely not to think he was

anything special! I never forgot that lesson in humility. That you

can never stop learning, that you can never know everything, that

you can never really be the best because human achievement is just

too complex."

Ray Szymarek Jr.

:

"I saw Gene Krupa for the

last time in Pittsburgh, Pa. in a twin bill Jazz Concert with Lionel

Hampton in Pittsburgh, Pa. at Heinz Hall. Wow you had to be

there to feel and get the percussion excitement that Gene Krupa

projected. Lionel Hampton and his band were on and they saved

Gene till the end of the second set to do two great numbers.

Hampton and Gene traded fours and had a lot of fun. But the Killer

Diller Knock Out Punch was the second chart, I think it was 'Ring

Them Bells' and Hampton got off the stage, knocked Gene's red light

circular spots on & all the house lights went dim. Gene

did his Krupa Magic in the special way that makes you want to get up

and shout GO GENE GO. He had the entire Heinz Hall audience in

the palm of his hands. I was there and there were a lot of

people who left the concert that night seeing Americas Number One

Ace Drummer Man show that he was a Drum Magnet. Gene the Man

projected and made you want to go out and dig Jazz. He will

always be remembered for being a great great gentleman and a truly

super drummer who contributed to Jazz like Buddy Rich, like Cozy

Cole and like Louis Bellson . Gene Krupa, just the name is

like seeing a sky rocket go so high and keep soaring. Gene Krupa and

his reputation will live forever. I want to thank our Shawn Crash

Martin for making this dedication page of Gene Krupa a happening."

Robin Morrison:

I'm 45 years old. The first

mention of Krupa that I recall was in freshman year high school,

when a sophomore told me what a waste of drivel was Krupa's Carnegie

Hall "Sing, Sing, Sing" performance which his Mother had played to

him as an example of top-flight drumming.

"He was just beating on the

tom-toms", said my friend.

This was about 1970. Hard

rock was coming into its commercial prime. Drumming was at a low.

Ginger Baker was the acknowledged King of Rock Drummers. Keith Moon,

during his more lucid moments, did his own emulation of That

Drumming Man, although we who idolized him at the time didn't know

that his was only that most sincere form of flattery: imitation.

Mitch Mitchell with Jimi Hendrix had his moments. Overall, the

concept of the Swinging Drummer was drowning in the rubble of drum

sets being shattered on stage amid the grotesque Bauhaus motifs of

concrete block, hard rock rhythms. Like trying to run a gymkhana in

an 18-wheeler. If it weren't for Keith Moon, Dino Danelli of the

Young Rascals, and that earnest red neck thumper, Ringo Starr,

"swing" - the concept, not the music - might have perished from the

drum throne.

Then the Quartet regrouped.

PBS-TV did a special on them. My best friend (a guitarist) and I

were enthralled. They displayed no pretension, only virtuosic

panache and an ensemble of shit-eating grins. Especially that wild

freak on the drums. When they played '"Avalon", the smile of his

face and the stroll of his snare were inseparable. He was so...

Cool! HOT! Cool... Cool in the by-then- abandoned Jazz Era style

which had been deemed passe, or at best campy, by the Woodstock

Generation (who nonetheless went nuts when Santana let them swing

mambo for awhile amid the mostly inept stomping of bands now rightly

called "dinosaur rockers").

We started hunting down

Goodman & Krupa records. One of these was Goodman with Joseph

Szigeti and Bela Bartok playing Bartok's "Contrasts for Violin,

Clarinet & Piano", and so I was exposed to modern classical

music by the same maniacs who'd turned Carnegie Hall into a dance

hall about the time this marvelous composition was written.

I saw their concert at

Ravinia in the Chicago suburbs, an outdoor venue that mostly

featured classical concerts and Broadway revues. Critics' assessment

of their work at that time was, for once, accurate. They played with

extraordinary ease and rhapsodic groove. By then, Krupa was so frail

he couldn't solo worth beans, but his ensemble groove was masterful,

still possessed of those simple yet rhythmically uncanny insertions

that delight the ear the way a roller coaster thrills the gut.

Krupa, as ruler of the Swing

Era's drumming elite, was often compared in contrasting to Bebop's

top drummers. Despite the masterful complexity and subtlety of the

latter's masters, especially when artists such as Tony Williams and

Roy Haynes presented more balanced approaches to spang-alang

drumming, Krupa always held a place of reverence and touched a nerve

of thrill above the bebop elite. I like to compare Krupa's

difference from, say, Philly Joe Jones, as the difference between

Coney Island and Disneyland. Disney is allegedly marvelous, and full

of more stuff than be seen in a day, but Coney Island is a pure kick

in the pants. A box of Cracker-Jacks, a waxpaper cup of Coca-Cola, a

good hot dog, and a chance to hold it all down while you ride the

big roller coaster. Krupa, whether inspired to complex rhythmic

subtlety or just laying down his patented syncopations, was always

kicking the gong around. He never took the fun out of finesse.

At Ravinia, we had front row

seats owing to Mom's connections with the Chicago Park District.

Midway through the concert as Gene was struggling his aged way

through a series of tepid solo breaks, my Dad, a typically taciturn

WWII vet of the John Wayne school of reserved demeanor, jumped up

from his chair (at front row we were in full view of EVERYONE),

raised his fist in the air, and shouted, "GO GENE GO!!!" Who was

this finger-poppin' daddy* posing as my Dad? Yeah, Krupa was too

cool. (*no, I am not a fan of the current retro swing ensembles like

the Cherry Poppin Daddies, Squirrel Nut Zippers. The reinvention of

mid-century swing as a Damon Runyon acid flashback is not for me,

thank you)

A tad later I saw the Sal

Mineo film "The Gene Krupa Story". Funny that this was one of the

first times I smoked pot, which caused the TV screen to visually

bend into a fish-eye lens look reminiscent of the first TV sets.

Great drumming, dopey film (no pun intended), but I had to love the

guys banging toms-toms and wearing tasseled fezzes chanting "Go

Gene, Go!" while Mineo did a great job of playing Krupa playing

drums.

Of all the video images or,

for that matter, personally remembered images of seeing Krupa live,

the best by far is Krupa playing... what's its name? the

killer-diller that opens with a reveille fanfare.... Bugle Call

Rag!... in "Big Broadcast of 37". It showed the perfect chemistry of

that original Goodman Band. Goodman's perfectly fleet fingerings of

highly sophisticated swing statements (methinks of him and Lester

Young as hopelessly indebted to each other like Siamese twins swung

at the hip) were perfectly contrasted by Krupa's fantastically

deranged (no other word serves descriptive justice) rhythmic

conflagrations. Harry James was a kick and all that, and gave that

brassy punch needed to not only raise the roof but knock a hole in

it so the moon and stars could shine on down from the mirror ball

revolving on high, but it was really the Ben&Geney Show, and I

would have given my left nut in a WWII combat injury to have been 19

years old in 1937 on the floor with a jitter-bugging girl while

those two raised hairs and heirs apparent from then until the day

Hot Swinging Jazz is but a musicological curiosity like contra

dances and work chants are today.

When I hear an obese

monstrosity like Pink Floyd as is so revered by my generation, and

ponder ponderosities like a Led Zeppelin, I wonder why and when the

youth of my crowd decided they wanted "heavy music". Moralizing

movies. Pontificating preachers. Hard rock noise blockades. Whenever

I hear or see Le Geneius, I feel I'm witnessing the peak of human

frivolity: serious, dead serious, about having a Real Good Time.

Jitterbug swing was an airy ballet wherein the dancers regularly

give each other an adroitly timed and perfectly placed kick in the

pants.

Finally, Krupa's the only guy

I've seen who looked at home in a bow tie. Even Miles Davis, the bon

vivant clothes horse, couldn't pull that one off.

Thanks for sharing the glow

which, like Roman aqueducts and Quixote-era windmills, is still in

use even to this day. Gone Gene, Gone!

Rim shot-press roll-hi-hat

sizzle groove off into the sunset....

And that experience remains the most treasured of my life.

Unfortunately (for me), I did not continue as a musician, and left

the business in '64. But the lessons that man taught me, about love

of learning, love of craft, and true humility, have guided me ever

since. Example: My lessons with him were on Fri afternoons, at 4pm

(after I got out of high school). When we were finished around

5-something one day, he decided to walk me outside as I headed for

the subway home. He asked me if I was headed uptown (Manhattan), and

I said no, I was going to get the train to Queens. I don't know what

possessed me, but I asked him, "Where are you headed?" And that's

when he absolutely floored me. He said (words to the effect) "I'm

going to MY lessons." I said, "What?" And he explained that he was

still studying, with Saul Goodman, the tympanist with the NY

Philharmonic! The master was STILL TAKING LESSONS! This was after

his greatest days and greatest accomplishments were behind him. He

was still eager to learn! There was not a SHRED of "I already know

it all" in him. In fact, he seemed genuinely not to think he was

anything special! I never forgot that lesson in humility. That you

can never stop learning, that you can never know everything, that

you can never really be the best because human achievement is just

too complex."

Ray Szymarek Jr.

:

"I saw Gene Krupa for the

last time in Pittsburgh, Pa. in a twin bill Jazz Concert with Lionel

Hampton in Pittsburgh, Pa. at Heinz Hall. Wow you had to be

there to feel and get the percussion excitement that Gene Krupa

projected. Lionel Hampton and his band were on and they saved

Gene till the end of the second set to do two great numbers.

Hampton and Gene traded fours and had a lot of fun. But the Killer

Diller Knock Out Punch was the second chart, I think it was 'Ring

Them Bells' and Hampton got off the stage, knocked Gene's red light

circular spots on & all the house lights went dim. Gene

did his Krupa Magic in the special way that makes you want to get up

and shout GO GENE GO. He had the entire Heinz Hall audience in

the palm of his hands. I was there and there were a lot of

people who left the concert that night seeing Americas Number One

Ace Drummer Man show that he was a Drum Magnet. Gene the Man

projected and made you want to go out and dig Jazz. He will

always be remembered for being a great great gentleman and a truly

super drummer who contributed to Jazz like Buddy Rich, like Cozy

Cole and like Louis Bellson . Gene Krupa, just the name is

like seeing a sky rocket go so high and keep soaring. Gene Krupa and

his reputation will live forever. I want to thank our Shawn Crash

Martin for making this dedication page of Gene Krupa a happening."

Robin Morrison:

I'm 45 years old. The first

mention of Krupa that I recall was in freshman year high school,

when a sophomore told me what a waste of drivel was Krupa's Carnegie

Hall "Sing, Sing, Sing" performance which his Mother had played to

him as an example of top-flight drumming.

"He was just beating on the

tom-toms", said my friend.

This was about 1970. Hard

rock was coming into its commercial prime. Drumming was at a low.

Ginger Baker was the acknowledged King of Rock Drummers. Keith Moon,

during his more lucid moments, did his own emulation of That

Drumming Man, although we who idolized him at the time didn't know

that his was only that most sincere form of flattery: imitation.

Mitch Mitchell with Jimi Hendrix had his moments. Overall, the

concept of the Swinging Drummer was drowning in the rubble of drum

sets being shattered on stage amid the grotesque Bauhaus motifs of

concrete block, hard rock rhythms. Like trying to run a gymkhana in

an 18-wheeler. If it weren't for Keith Moon, Dino Danelli of the

Young Rascals, and that earnest red neck thumper, Ringo Starr,

"swing" - the concept, not the music - might have perished from the

drum throne.

Then the Quartet regrouped.

PBS-TV did a special on them. My best friend (a guitarist) and I

were enthralled. They displayed no pretension, only virtuosic

panache and an ensemble of shit-eating grins. Especially that wild

freak on the drums. When they played '"Avalon", the smile of his

face and the stroll of his snare were inseparable. He was so...

Cool! HOT! Cool... Cool in the by-then- abandoned Jazz Era style

which had been deemed passe, or at best campy, by the Woodstock

Generation (who nonetheless went nuts when Santana let them swing

mambo for awhile amid the mostly inept stomping of bands now rightly

called "dinosaur rockers").

We started hunting down

Goodman & Krupa records. One of these was Goodman with Joseph

Szigeti and Bela Bartok playing Bartok's "Contrasts for Violin,

Clarinet & Piano", and so I was exposed to modern classical

music by the same maniacs who'd turned Carnegie Hall into a dance

hall about the time this marvelous composition was written.

I saw their concert at

Ravinia in the Chicago suburbs, an outdoor venue that mostly

featured classical concerts and Broadway revues. Critics' assessment

of their work at that time was, for once, accurate. They played with

extraordinary ease and rhapsodic groove. By then, Krupa was so frail

he couldn't solo worth beans, but his ensemble groove was masterful,

still possessed of those simple yet rhythmically uncanny insertions

that delight the ear the way a roller coaster thrills the gut.

Krupa, as ruler of the Swing

Era's drumming elite, was often compared in contrasting to Bebop's

top drummers. Despite the masterful complexity and subtlety of the

latter's masters, especially when artists such as Tony Williams and

Roy Haynes presented more balanced approaches to spang-alang

drumming, Krupa always held a place of reverence and touched a nerve

of thrill above the bebop elite. I like to compare Krupa's

difference from, say, Philly Joe Jones, as the difference between

Coney Island and Disneyland. Disney is allegedly marvelous, and full

of more stuff than be seen in a day, but Coney Island is a pure kick

in the pants. A box of Cracker-Jacks, a waxpaper cup of Coca-Cola, a

good hot dog, and a chance to hold it all down while you ride the

big roller coaster. Krupa, whether inspired to complex rhythmic

subtlety or just laying down his patented syncopations, was always

kicking the gong around. He never took the fun out of finesse.

At Ravinia, we had front row

seats owing to Mom's connections with the Chicago Park District.

Midway through the concert as Gene was struggling his aged way

through a series of tepid solo breaks, my Dad, a typically taciturn

WWII vet of the John Wayne school of reserved demeanor, jumped up

from his chair (at front row we were in full view of EVERYONE),

raised his fist in the air, and shouted, "GO GENE GO!!!" Who was

this finger-poppin' daddy* posing as my Dad? Yeah, Krupa was too

cool. (*no, I am not a fan of the current retro swing ensembles like

the Cherry Poppin Daddies, Squirrel Nut Zippers. The reinvention of

mid-century swing as a Damon Runyon acid flashback is not for me,

thank you)

A tad later I saw the Sal

Mineo film "The Gene Krupa Story". Funny that this was one of the

first times I smoked pot, which caused the TV screen to visually

bend into a fish-eye lens look reminiscent of the first TV sets.

Great drumming, dopey film (no pun intended), but I had to love the